This is the first in series of articles that grew out of the research that went into my workshop on the ur-form of what we call the Bradel given to students and staff at the University of Iowa Center for the Book and University Libraries on October 1 -2, 2021. As part of the William Anthony Lecture Series it was supported by the Nadia Sophie Seiler Fund and the University of Iowa Libraries & Center for the Book.

I had originally considered formally publishing this in a journal, but for a variety of reasons I am serializing here at the Pressbengel Project, perhaps somewhat less formally. Advantages of online publication include the ability to embed video... When completed, the posts will be combined into a downloadable form. The title, "Disbinding Bradel" was originally suggested by Jeff Peachey. I am also grateful to Susie Cobbledick, Guild of Book Workers Journal co-editor, for her thoughts on converting my hand-out into an article.

|

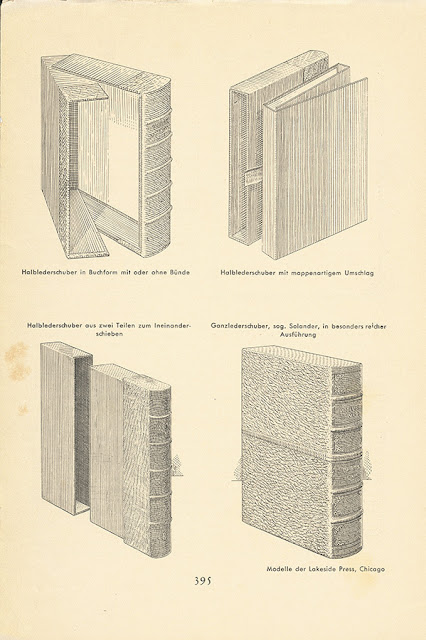

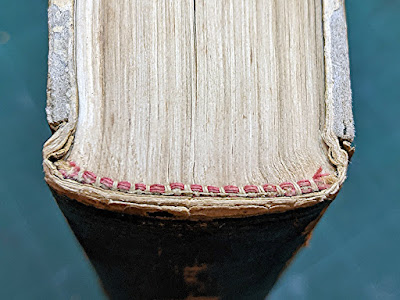

| Here, book closed, the one-piece spine and connector construction. |

The low profile of the German element in American hand binding is hard to understand, although several factors can be identified. German-tradition binders have added little to the English-language literature of binding; and little has been translated from German. Much of the German contribution to the common pool has been forwarding and technique rather than design finishing. The German tradition has contributed little to the philosophy of binding in America (this comes largely from the English Arts and Crafts movement); and in aesthetics American binders have tended to follow the French in aping painting and the fine arts.

A type of binding having a hollow back, and not unlike a library binding, except that it is considered to be temporary. The style was originated in Germany by Alexis Pierre Bradel, also known as Bradel l'ainé, and also as Bradel-Derome, son-in-law and successor to Nicholas-Denis Derôme. The style was taken to France sometime between 1772 and 1809. Bradel bindings generally have split boards into which are attached the extensions of the spine lining cloth. The edges are uncut, sometimes with the head edge being gilt. They generally have a leather or linen spine. In France the style was known as "Cartonnage à la Bradel", or as "en gist".

The German term for the three-piece case, 'gebrochener Rücken', meaning literally 'broken back', is presumably a reference to splitting a one-piece case into two sides with a connecting spine-piece. This meant that it was possible to have a thinner flexible spine-piece that allowed the book to open whilst having a rigid board on each side to support and protect the book block, a dual function that was not possible with the one-piece case. The three-piece case was known in France at the end of the eighteenth century as the ‘reliure Bradel’ or ‘cartonnage à la Bradel’ having been introduced there, apparently, by a member of the Bradel family.

The type of binding that has become known in Paris, was imported from Germany by a bookbinder who alone made it for some time, with this type of binding acquiring a certain reputation. When well executed, it has a number of advantages: it looks good enough on a library shelf; it is clean and can be made with solidity; the leaves are not so that works can be read for a long time as they were simply bound, and when it is they retain wide margins. Here's how it's done... (p 209)

We are familiar with the so-called, German-inspired 'Bradel' bindings "because, says Lesné, Bradel was one of the first bookbinders who started to make them and because he makes them well enough". That being said, in another passage of his poem, he mentions him again, this time in a much less benevolent manner, speaking about those binders who claim to have invented some new system:

With the help of a very amphibological jargon, he impresses the fools, and exposes himself to criticism; Such are the processes of Bradel, Cabanis, who charm the province and even all Paris. The one binds in the German style, And the other sews as in Holland.

Our poet speaking in the present tense, it seems obvious that the author of these bindings must have lived in 1820, but how do we identify which one of all these Bradels he was referring to? We give up on that, as well as we give up on trying to identify the other one that he quoted and whose talent presumably equaled that of Chaumont and Deboisseau, well regarded binders of the restoration period. (Thank you to Benjamin Elbel for this translation)