Before we dive into the review of the literature, below the key attributes of the Pappband structure, what we in the English speaking world refer to as the "German case binding" or "Bradel".

To find the documented origins of this structure, we will now travel back in time to the earliest German manuals, and work our way forward into the early 20th century when modern, comprehensive manuals codified many structures and processes. With one exception, I will not trace other traditions, e.g. the French, but welcome others with the language skills and training to do so.

Like many early bookbinding manuals, the German manuals are minimally illustrated and written for a trade that would have learned the techniques starting as apprentices working at the bench under the guidance of journeymen and masters. Those manuals would have served as references. If illustrations were included, they were generalized depictions of binderies with various processes shown, such as frontispieces, some diagrams for e.g. folding signatures or of tools, and fold-out plates that showed a variety of tools. That changed in the mid-/late 19th century when in addition to diagrams, they were illustrated with the latest in bookbinding and related machines, sometimes including the hands of the maker and operators. Readers would have been familiar with what was being described. They are far removed from many of today’s manuals with step-by-step, fully illustrated instructions.

The manuals would begin by describing foundational steps such as beating, folding, and sewing in general terms, followed by specific binding types, referencing the steps, especially where they differ. The appropriate endpaper construction for these “Pappband” bindings would be selected from the simpler ones, often plain, but also colored. These could be hooked around the first and last sections, be a plain double folio sections, and later, a tipped-on folio. There could also be a combination of hooked paper guards and/or waste sheets, and later sewn cloth hinges that might be selected. Spines would be lined after rounding/backing and endbanding with strong paper, or in the case of heavier books parchment or cloth under the paper that might extend onto the guards.

|

| Title page to Zeidler, 1708. |

Prediger in his

Der in aller heut zu Tag üblichen Arbeit wohl anweisende accurate Buchbinder und Futteralmacher (1772), while discussing paper board bindings, describes fraying out the cords using a

fray shield (Aufschabeblech), and adhering them to the waste sheet/guard after sewing and gluing up the spine. (pp. 91-93). These steps were also described in his section on parchment covered bindings where we begin to encounter the spine piece. Here, a piece of card would be cut taller and wider than the spine. Various units were used to describe this extra width in the literature, from 2-3 fingers wide, to 1-3 “Zoll” (similar to inches), to centimeters. The spine would then be measured, and the marks transferred to the card denoting the top of the shoulder. A second set of marks equivalent to the distance from the top to the base of the shoulder would then be made to the outside of the first marks. The card would then be folded (Rückenbrechen; first use of term “brechen”) at the marks so that when rounded it fit tight to the spine.

|

| "Rückenbrechen" in Prediger, p. 113. |

This spine piece would then be adhered to the guards and then the boards adhered on top, lining up with the fold at the bottom of the shoulder. Then trim to size and cover. While described in the context of a parchment binding, the structure and steps are like those of what would be called a “Pappband” (paper binding). (pp. 106-8, 113-)

|

| Title page to Prediger, 1772. |

This aligns with the description found in the article "

Die Berechtigung des Pappbands" (1906) that places the origins during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763, and known in North America as the French and Indian War) where it viewed as an austerity

Ersatz for parchment bindings, with similar forwarding techniques for the construction of the spine and cover. The Napoleonic wars that followed had an even greater impact, so that the "Pappband" became the German all-purpose binding structure for books and libraries.

Bücking’s Die Kunst des Buchbindens (1785) in discussing the “Pappband” describes a similar treatment of the spine, but rather than fraying out the cords and adhering to the guard, he first makes the spine piece, laces the cords through before adhering the spine piece to the guards, and finally gluing the cords on top of that. Finally, the boards are attached. (pp 266-67)

|

| Title page to Bücking, 1785. |

[s.n.] Anweisung zur Buchbinderkunst, (1802) writes that after backing…, fray out the cords and paste/glue down on stubs (Flügel/Falz) (pp. 128-9). Next, create the wrapper from one piece of board. To measure width of spine, flatten the spine of the text block, mark, and break/crease (brechet, gebrochene) at shoulder and to the outside of the first creases to create the wrapper.

|

| "Brechet" and "gebrochene" from Anweisung, p. 138. |

Then. apply glue to stubs, fit the wrapper, and place in the press. Next, tear away the excess paper from stubs, make cuts in stub for turn-ins at head and tail, and trim to final size. Finally, cut the covering paper to size including turn-ins, paste out and apply, also turning in. Afterwards, put down board sheets. If thicker boards are desired cut thinner board to the needed height with stubs to either side. Then. break per earlier example, edge-pare the long sides, apply to stubs of endpapers, and put in press. Next, cut thicker boards to size, apply to spine piece and press; Covering steps would be the same as with the one-piece wrapper. (pp. 138-40) The text also provides general tips regarding the kinds of papers used for covering, the use paste as adhesive, waiting until dry before pressing so that the covering (e.g. paste paper) doesn’t stick to the press boards, working the covering across boards and spine, turning-in, and putting down the board sheet (anpappen). (pp.148-50)

|

| Title page to Anweisung, 1802. |

Greve’s Hand- und Lehrbuch der Buchbindekunst (1823) is written in an epistolary style that does not differ substantively from the preceding texts, but is the first to mention of the term “gebrochenen Rücken” (p. 327) in this way.

|

| "Gebrochen", "gebrochener Rücken" in Greve, p. 327. |

It is also the first to mention (later with H. Bauer (1899), C. Bauer & A. Franke (1903), and A. Franke (1922)) that when adhering the spine piece, the adhesive should only be applied from the outer shoulder folds outwards, leaving the shoulder NOT adhered to the cover. Further, it is also the first to explicitly connect this structure to coverings other than paper, mentioning to leave more space in the groove dependent on thickness of covering material, as well as the sequence for covering if a quarter binding. (pp. 325-334)

|

| Title page to Greve, 1823. |

|

| Bradel in Le Normand, pg. 139. |

It is the only text that references a “Bradel”. After sewing and backing, the binder is directed to make an “Einlag-Papier”, the term used instead of “gebrochene Rücken”. This spine piece is made by measuring the width of the spine, then folding at the shoulders and in the opposite direction at the base of the shoulder. After rounding to the shape of the spine, adhesive is brushed onto the guard to the shoulder taking care not to get it onto the endpaper and then the piece is fit snuggly to the text block and placed in a press between boards. Next, the boards are attached to the spine piece, pressed, and then trimmed to size before the next steps of covering. (p. 141-2)

|

| Title page to Le Normande, 1832. |

|

| Title page to Schäfer, 1845. |

Thon’s Die Kunst Bücher zu binden (1856) continues the use of the term “gebrochener Rücken” for the spine. (p. 208)

In a later edition (1865), he describes the original one-piece construction of this spine piece, but for the first time, the 2-piece construction we now use where the spine stiffener is glued to a piece of heavier paper. In this, the spine stiffener is cut from card to the width of the spine and glued onto a wider strip of heavy paper so that the width would be equivalent to that of the then traditional one-piece spine piece. Like the traditional, it would be edge pared and adhered to the guards. Like Greve it mentioned adjusting the board position for the thickness of the covering material. Thon was also the first to describe this structure for use as a case binding, suggesting that one attach the spine piece to the guards with two dabs of glue, then attach the boards, cover, and pop off to stamp the cover or spine. Before this, labels would have been used. The case is then reattached properly and the ends put down. Thon also described creating the case without the connecting strip, mentioning that this was suited to mass production and that a hollow could be used to secure it to the text block. (pp. 331-342)

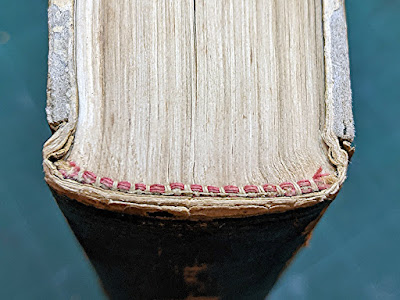

So, the "gebrochene Rücken" evolved from example at left to that at right:

|

On the left, the "ur-Bradel one-piece spine, on the right the later

2-piece. The image is from the first book structure I learned

and bound during my 1984 internship in Nuremberg. |

|

| Title page to Thon, 1856. |

L. Brade’s Illustrirtes Buchbinderbuch (1882), no connection any Bradel, repeats the two variants of spine piece described by Thon. In describing the newer construction using a spine stiffener of card with a heavy paper strip to connect it to the text block, he points out that it is easier to apply and better suited to thin books. While no reason is given, the paper folds better and is more flexible resulting in better openability. Brade also mentions the suitability of the structure for bindings covered in paper, cloth, some leathers, and parchment. (Pg. 202) Published in numerous editions, it remained largely unchanged on this topic, e.g. the 1892 edition.

|

| Title page to Brade, 1882 |

Adam was one of the most prolific German bookbinding instructors and authors of the late 19th early 20th centuries, arguably responsible for much of the codification of techniques that resulted in Luers, Rhein, and Wiese.

Both versions of the spine piece (1-piece card, 2-piece paper and card) and the method of attachment were described in

Systematisches Lehr- und Handbuch der Buchbinderei (1882) and

Der Bucheinband, seine Technik und seine Geschichte (1890).

In the 1882 text, Adam writes to "cut “gebrochener Rücken” from card slightly longer and 2 finger widths wider/ side than spine of book, then edge-pare the long edges so as to avoid step under paste down. To stiffen the spine further, e.g. a large, heavy book, cut a strip of heavy paper/thin card height of gebrochener Rücken, then measure and mark width of spine centered on strip at top and bottom, score and fold. Finally make the parallel folds for the groove, also accounting for thickness of covering material. (pg. 279)

The more modern alternative described a few pages later is made of a.spine stiffener (Einlage) cut to width of spine and glued centered on heavier paper that is wider to allow for attachment to text block and of boards. (pg. 281) For both styles, apply paste/glue to stub of waste sheet (Flügelfalz) with frayed out cords pasted on top or bottom of “Flügel” of the Rücken (Einlage to inside), rub down, apply boards and press. Trim fore-edge, cover...

Other things mentioned include that for this structure, the shoulder created by the swell from sewing was usually sufficient (pg. 155), and that the cover was “eingehangen“ (cased-in) a departure from the traditional in-boards/built up method. Due to the flexibility of the “gebrochener Rücken”, it could easily be applied to both.

|

| Title page from Adam, 1882. |

In the 1890 text, Der Bucheinband... these descriptions are largely unchanged from the 1882 text.

|

| Title page to Adam, 1890. |

Adam’s Die praktischen Arbeiten des Buchbinders (1898), is the first German manual that was translated into English as

Practical Bookbinding (1903). It is also the first to illustrate the “gebrochener Rücken” spine piece in the more modern version with a card strip adhered to a wider strip of paper describing it as a “Pappbandrücken” (paper binding spine). In the English edition. This was referred to as the “springback” because it was not adhered to the spine itself and formed a hollow. It extended over the spine and underneath the cover (4-5 cm wider on each side) with “backing”, a "spine stiffener" of same material, exact width of spine. It is not to be confused with the “Sprungrücken” (springback ledger-style).

|

"Gebrochener Pappbandrücken" (1898) at left,

translated as "spring back" (1903) at right.

Note that the "spine stiffener" is to the inside of the connecting paper strip. |

|

| Title pages from Adam, 1898 & 1903. |

H. Bauer’s Katechismus der Buchbinderei (1899) written in the form of a dialog describes the spine piece as being made from 2 pieces of card, one the width of the spine, the other wider. As with this structure, the narrower piece was adhered centered to the wider piece. Unlike most other descriptions (excepting Greve (1823), C. Bauer (1903), and A. Franke (1922), it was only adhered to the guards from the outer folds at the base of the shoulder only. (pp. 137-39)

|

| Title page from H. Bauer, 1899. |

C. Bauer’s Handbuch der Buchbinderei: eine leichtfassliche Anleitung zur Herstellung (1903), edited by A. Franke is like H. Bauer, but also mentions that the weight of the card used for the wider strip of card that is adhered to the guards should be determined by the size and other properties of the text block. It also described the narrower strip that is the width of the spine as an “Einlegerücken”, today referred to as the “Rückeneinlage”. The structure can also be the basis for the cloth covered binding, with simplifications for use in large scale trade binding. (pg. 107)

|

| Title page from C. Bauer, A. Franke ed., 1903. |

L. Brade's Illustriertes Buchbinderbuch (1904), in the chapter on the Pappband, describes forming spine stiffener, the "gebrochene Rücken" by folding the card or paper using the term "brechen" (breaking / folding) – "hierauf wird der Rücken gebrochen, wozu man sich eines nich zu scharfen Falzbeines und eines Lineals bedient ..." (now we form the spine by "breaking" for which we use a not to "sharp" bone folder and a straightedge)

%20a.jpg) |

| Title page from L[udwig] Brade, 1904. |

%20b.jpg) |

| Section from Brade on forming the gebrochene Rücken. |

"Der Pappband im Gewande der Zeit (pp 86-89)", an article in the

Archiv für Buchbinderei (1909) describes the background of the "gebrochene Rücken“ in detail with lots of "biegen" and "brechen" (creasing and folding).

|

Detail from pg. 86 of the article. The process description

continues on the subsequent pages ... |

C. Bauer’s Die Buchbinderei: eine leichtfassliche Anleitung zur Herstellung (1922), edited by A. Franke, and the 9th edition, described the same structure for the “gebrochene Rücken“ as in the previous item (1903) with both parts being made from card. The long edges were edge pared, much like in the 19th century. While the main application seemed to be on cloth bindings, C. Bauer wrote that the original paper covered “Pappband” held up quite well, but the ones produced during [WW I] tended to go back to a bookbinder for replacement. He attributed this to their being mass-produced industrial products. (pg. 142)

|

| Title page from C. Bauer, A. Franke ed., 1922. |

Moving forward in the 20th century, the structure itself has remained essentially unchanged. Endpapers went towards bi-folios, with a hooked waste sheet to fan the frayed cords or tapes out on. Cloth hinges were also used on these endsheets, sewn in or tipped on with a decorative on over the stub. In short, there were lots of possibilities, but the uses of this structure were increasingly as case bindings. In terms of whether to apply adhesive all the way to the edge of the shoulder or not, most mid-20th century and newer manuals describe the former. Manuals describing this include Luers, Fröde, Moessner, Rhein, Wiese, Moessner, … An exception appears to be Morf who described applying the adhesive from the base of the shoulder outwards. The “bible” to the Pappband structure as currently used is Siegfried Büge’s Der Pappband (1973) that references the historical origins, and describes it for fine paper bindings and what we call the “millimeter” binding (Edelpappband). The term “Bradel” was not mentioned. However, the term “Bradel” is not unknown in Germany, due in part to translations and learners traveling to take advantage of workshops and other training. Reviewing contemporary manuals (1960s onward) reveals that there are differences from the German, but that these are in the details and nuances.

As an example, the

German case binding structure I describe can be used for covering in paper, cloth, leather, vellum, and combinations thereof. It can be built up on the text block in-boards) or constructed as a case. The

Edelpappband (noble paper-covered binding) has leather trim along some combination of board edges and spine, the Danes call it "

Rubow" after the binder who made it popular there, and the Anglo-Americans call "millimeter" binding because of the amount of cloth/leather/vellum trim showing after covering. This is distinct from the

Danish "millimeter" that is like the modern French "Bradel

and “

simplified” built up on the text block. There is also the explanation I was given by Suzanne Schmollgruber, formerly of the Centro del bel Libro in Ascona, CH, is that in modern usage, the "

Bradel" is now used to describe bindings using the "gebrochener Rücken" that are built up on the text block, whereas "mit aufgesetzten Deckeln" is used to describe the "

three piece case binding" variety.

Finally, if one were to do a dissection of a full paper or cloth (not separate spine covering), one should not be able to tell the cased apart from the in-boards. I use both methods, preferring the in-boards on smaller, more delicate books as I find it easier to work precisely. Sometimes, I'll work in-boards, attaching what will be the cover to a waste sheet, then removing to stamp... as a case, and then reattach.

Below are some good readings on the historical structure in English:

- Caswell, Bexx and Patrick Olson. "Germany and the Modernization of Bookbinding: Evidence from Michigan State University's Criminology Collection." Found in: Miller, Julia (ed.). Suave Mechanicals: Essays on the History of Bookbinding. Volume 5. Ann Arbor: The Legacy Press, 2019.

- Cloonan, M. V. Early Bindings in Paper: A Brief History of European Hand-made Paper-covered Books with a Multilingual Glossary. Boston, MA: G.K. Hall, 1991.

- Frost, Gary. (1982). "Historical paper case binding and conservation rebinding". The New Bookbinder, 2, 64-67, 1982.

- Pattison, Todd and Graham Patten. "Confusing the Case: Books Bound with Adhered Boards, 1760 –1860". Found in: Miller, Julia (ed.). Suave Mechanicals: Essays on the History of Bookbinding. Volume 5. Ann Arbor: The Legacy Press, 2019.

- Rhodes, B. "18th and 19th century European and American paper binding structures: a case study of paper bindings in the American Museum of Natural History Library". Book and Paper Group Annual, 14, 51–62, 1995.

As always, I welcome questions, references to additional sources, and other thoughts via the comments. Just remember to cite those sources. Thank you.

%20a.jpg)

%20b.jpg)